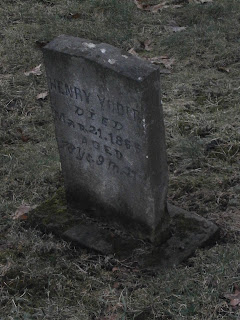

This beaten and battered headstone exemplifies the stark, straightforward relationship that early Americans had with death. Children often did not live past early childhood, disease was not understood or easily prevented, and life was shorter and much more dangerous than it is now. The world was often bleak and hard, and God's judgement was used to explain the tragic randomness of death. With life being so unpredictable, our forebearers were closer to and more realistic about death and dying.

The death's head on the stone is flanked by a pair of angel wings, which is graduated from the more viscerally morbid skull flanked by crossbones. The wings show the promise of heaven amid the brutality of life and death. To the right of the skull and wings is an hourglass, symbolic of our limited amount of time on earth, and the words 'Fugit Hora'. This saying is Latin for 'The hour flies' or 'Time flies'. It asks passersby to think about the brevity of life and how to make it count. When looking at the left side of the headstone, the phrase 'Memento mori' can be seen. At one time, this phrase was highly common on headstones, and it translates to 'Remember that you will die'. It asks the living to always remember that your time is limited, and to live life as best you can, but always be prepared to die. Say what needs to be said, do what needs to be done, and always live with this reminder in the back of your head. The crossbones accompanied by this saying drives this reminder home.

As American religious, funereal, medical, philosophical, and personal views evolved, the focus on bodily mortality disappeared, and the focus on the importance of the life lived and memories left behind became the prominent mode of mourning. We can learn from our forebearers, though: We all will die, and we should live while we are alive.